Prospect House, 32 Sovereign Street, Leeds, LS1

"Why would you order a taxi from where I don't know where it is? Why didn't you order it from the station?" The person on the phone outside Leeds station was having a bad day. Don't drive to Leeds I was told but public transport apparently carried its own frustrations. I left him to it, and headed towards Prospect House which I was delighted to discover was barely five minutes walk from the station. If only they could all be this easy.There's not much contemporary information about Realtime Games. CRASH interviewed the three founders, Ian Oliver, Andrew Onions and Graeme Baird, in June 1986 on what was more or less the company's second birthday, and that's it. Fortunately the company became a bit more outgoing in 1988. Twice as outgoing in fact. They gave two interviews. One to AMIGA COMPUTING (October 1988 page 20) and another to POWER PLAY magazine. It's a lovely four-page piece with just one snag. It's in German. Now, my schoolboy German doesn't go any further than «Noch ein Bier bitte» but fortunately I know a computer that speaks it fluently and you can read the translated piece here.

Realtime Games Ltd came out of a computer science course, like Design Design, but Realtime were in Leeds rather than Manchester. The founding trio always gave a birth date for their company of 8th May 1984, during final exams, after their first game was finished. 3D Tank Duel, based on Battlezone by Atari, was started around Christmas 1983 and finished the following Easter; just in time for the 11th ZX Microfair on 28th April 1984. The game and company were both named just a few hours before their debut, on the train from Leeds to London according to CRASH (August 1984 page 84).

|

| May 2022 |

3D Tank Duel sloped on to the market with little fanfare. CRASH printed a brief preview in the June 1984 issue with the disclaimer: "We first met Andrew Onions, one of the duo who make up Real Time, because his parents live only a few doors away from the CRASH offices." This would have been when CRASH was still based in editor Roger Kean's house at 85 Old Street, Ludlow. The preview would also have been written around the time CRASH was engaged in a spat with PERSONAL COMPUTER GAMES over objectivity. (PCG criticised CRASH for printing an interview with programmer Steve Turner, of Graftgold that was conducted by their publisher Andrew Hewson, of Hewson Consultants.) The note about Andrew's parents could be a reaction to the objectivity spat or it could just be part of CRASH's fanzine-like charm. CRASH had a good relationship with Realtime. 3D Tank Duel gets a positive review in the August 1984 and a competition. It took until December for most other magazines to review the game. SINCLAIR USER and COMPUTER & VIDEOGAMES both directly compared 3D Tank Duel to Quicksilva's official licenced conversion, and the Realtime game came out on top. POWER PLAY notes it sold around 7000 copies in all. 3D Tank Duel had a long shelf life. It was licenced to the 1985 Soft Aid compilation to raise money for the Ethiopian famine appeal. The following year it was licenced to Elite for their £2.99 classics range, and then in 1989 to Zeppelin games who renamed it Battle Tank Simulator.

The competition blurb in the August issue of CRASH included some enticing details of future Realtime games: "Several more projects are under development including a multi-section 3D space battle game and some spite games as well as a realtime graphics adventure. The latter is very much on the drawing board, but the 3D Space battle is fairly advanced, and judging by some of the graphics we have seen, looks like being pretty amazing." It was. Despite the dearth of home computer clones of arcade games like Space Invaders or Frogger, few companies tried a version of Atari's Star Wars arcade game. It may be that 20th Century Fox was better at stepping on copyright infringement or it might just be that software companies were put off trying by the obvious technical limitations; games which did come out focused on the trench section, like Blade Alley by PSS or Death Star by Rabbit. When CRASH got an early look at Realtime's new game they got terribly excited:

"Oddly enough the lads have been working along very similar lines to the Design Design programmer Simon Brattel (see next piece!) but whereas Simon has gone out of his way to show just how astonishingly fast line graphics on the Spectrum can be done, Realtime have concentrated more on moving larger objects In 3D. The new game is due out shortly after this issue hits the streets and is called STARBURST (at least, it is at the moment). In effect it is an extraordinary version of the top arcade original Star Wars and features the three main screens."

Starburst was quickly renamed 3D Starstrike and became a well deserved hit. It's always difficult to explain now why games were remarkable then. Today 1983's 3D Deathchase is a juddering, low-resolution mess with a tooth-grinding soundtrack of clicks and beeps but if you come and stand over here, I could try and explain why it was a Return of the Jedi game at a time when everyone wanted a Return of the Jedi game and, ultimately, better than Atari's own Return of the Jedi arcade game. 3D Starstrike is remarkable mainly because it's fast. But, it's also important to note it's fast in a different way to Design Design games like Invasion of the Body Snatchas! or Dark Star. It's moving bigger graphics around and there's near constant sound (well, clicks and buzzes) and it's really colourful. 3D Starstrike also copies all three stages of the Star Wars arcade game, not just the trench level. Plus, Realtime have added their own spin to the game, as with 3D Tank Duel, by one-upping the arcade game and adding in a short fourth level which involves destroying the reactor as you fly through the chamber. And Oliver Frey painted the cover so the Realtime boys knew good art when they saw it.

3D Starstrike was hugely successful. "We made so much money with Starstrike that we lived off it for months without doing anything big," is one of the quotes in the POWER PLAY article. The game certainly seems to have funded 12 months of flitting about. 1985 saw an Amstrad version of 3D Starstrike plus a version for the budding Enterprise format. And a different game, for a different doomed format -the Sinclair QL- Knight Flight. What it didn't see was a game called Argonautica. ZZAP64! described this as, "not a conversion of [3D Starstrike], but a new arcade adventure... starring that legendary hero Jason (as in Jason and the Argonauts) in search of the Golden Fleece. The game contains some 30 screens of highly detailed graphics along with some equally detailed gameplay and should be available just after Christmas." (Christmas Special 1985 page 65). Just after Christmas came and went. The February 1986 issue of ZZAP!64 carried an advert. There was more information in the March 1986 issue: "The game is a multicharacter arcade adventure played over several scenes of scrolling locations and involves some 'incredibly detailed backgrounds'. Realtime are having big problems in cramming the whole thing into the 64's memory and it could well end up being a two cassette game." And that was the end of Argonautica.

Starstrike II arrived in the early summer of 1986. "When we ran out of money, we rushed to write Starstrike II," is one comment in the POWER PLAY interview. This time clever programming allowed the vector graphics to be filled in and features much more solid looking objects. It must have been frustrating to be working on Starstrike II and see I, Of The Mask reviewed around Christmas 1985 with it's very similar graphics style. In the wider world, the software market was changing. The success of Starstrike in 1984 could comfortably support a small three-person company but only 18 months later it proved difficult to persuade distributors to put the new game in shops, as CRASH revealed:

"Certain large chain stores are only now accepting Starstrike [II]on their shelves, having refused to handle its predecessor. And a few hairy financial moments were experienced before its release, when large sums of money bad been committed to advertising, leaving very little cash to live on while the game was finished off." (CRASH interview).

Operating as a small company was becoming harder. It proved easier to sell the Amstrad version rights to Firebird rather than try and market and sell Starstrike II directly through Realtime. There's a moment in the CRASH interview when writer Hannah Smith directly asks the trio:

"Had they not been tempted to become a facilities house along the lines of Denton Designs who produce games to contract, for others to publish? Definitely not, said Andrew Onions."

Definitely not. But Christmas 1986 saw the release of Realtime's conversion of Starglider for Rainbird, for whom Realtime had become a facilities house. This is obviously speculation but in the CRASH interview the paragraph after the flat "definitely not," talks about Realtime's conversion work for the Enterprise computer with a reference to how: "Getting paid has proved a little problematic, and all three now adamantly insist that this line of work is not one they are keen to pursue." The process of working with Firebird to release the Amstrad version of Starstrike II in autumn 1986 must have been good enough to change their attitude and lead them to accept the Starglider conversion job from Rainbird; like Firebird a division of Telecomsoft. After this Realtime would only work as a developer. They worked for Ariolasoft to convert Starfox to the Spectrum and Amstrad in 1987. Then it was back to Rainbird who published Realtime's magnificent opus.

Carrier Command is a real-time, open world, combat and resource management game (the Mona Lisa is a painting of a smirking woman in a room), and it quickly became a defining 16-bit game and showed what the Amiga and Atari ST could do. So it was something of a surprise when Realtime also converted back to the 8-bit Amstrad and Spectrum. Reviewers couldn't find enough nice words to use about Carrier Command. Except for AMSTRAD ACTION who didn't review the game because "we never got a review copy." You could have walked to the shops, guys.

Battle Command a sort of sequel followed in 1990, although development had started concurrently with Carrier Command according to THE ONE (May 1990 page 98) There were also two unreleased games. EPT, mentioned in the 1988 POWER PLAY interview and again in THE ONE where its fate is summed up as:

"Realtime says it has no plans to resurrect it, and isn't even sure who owns the publishing rights anymore. It could never have been sold in America under that name anyway: the US public associates the initials with a popular product called Early Pregnancy Test'."

The other unreleased game was Duster due for release by Mirrorsoft on their Imageworks label. Duster seems to have done for Realtime Games but there's frustratingly little information available. Games that Weren't cites reports by AMIGA POWER and ST FORMAT, and the limited timeline available runs:

May 1990. Duster is "30% complete," according to THE ONE.

Summer of 1991. Realtime "lose" Andy Onions according to Games that Weren't.

July 1991, an ST FORMAT news story

"a change of direction within the company," Realtime "would not be able

to complete the program within the projected scale," Rowan Software

will take over programming.

December 1991. Mirrorsoft are liquidated.

|

| NEXT GENERATION September 1995 page 53 |

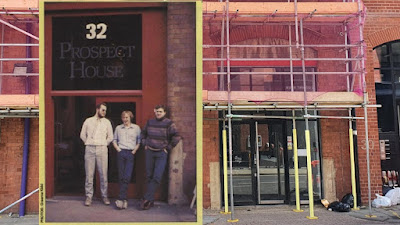

Sovereign House was being refurbished when I passed by, as you can tell from the picture up the page. It was difficult to get any sort of shot of the frontage with all the associated scaffolding and netting blocking the view but I was able to do a compare and contrast with the photo of Ian Oliver, Andrew Onions and Graeme Baird printed in CRASH issue 25.

However, it turns out I was missing one key piece of the puzzle. The German POWER PLAY interview includes this information:

»Until then we were working in a particularly bad area, where there were dozens of stray dogs, garbage on the streets and other inconveniences. With the money we earned through Starstrike, we first got better offices«. Incidentally, Realtime is still based in the offices they moved into in January 1985.

That interview was pretty chaotic. Writer Boris Schneider describes it as »That was one of my wildest interviews,« »the four programmers kept talking at once, contradicting each other and suddenly all agreeing again. It can no longer be reconstructed who actually said what. But it was a lot of fun!.« Adverts for Realtime games always list the 32 Sovereign Street address so, not unreasonably, I assumed the January 1985 comment was a misheard reference to when Realtime moved into Sovereign House, and then I found this tweet:

A modern day view of 23 The Calls in central Leeds. This was the office address of Realtime Games, creators of Carrier Command!🚢I've walked past it many times and had no idea. I wonder what other game developers or publishers had a presence in Leeds back in the 80's and 90's? 🤔 pic.twitter.com/fNakKJgcIL

— Jonathan Thomas (@RetroRacing) August 8, 2021

23 The Calls, Leeds

What's the deal?

1. When it was publishing games, Realtime was always based in Sovereign House and they moved to 23 The Calls after they became a developer for hire. The comments about dogs and new offices are bits of interview banter that got lost in translation.

2. Realtime moved into Sovereign House in 1984. Then, in January 1985, fed up with endlessly dealing with packs of stray dogs, etc and newly flush with Starstrike cash they moved to 23 The Calls but decided to keep using Sovereign House as their business address.

3. Realtime moved into a bad area while at university and then set up their business in Sovereign House, the January 1985 date is a misunderstanding. Later the company moved to 23 The Calls.

4. Something else.

As Jonathan Tomas points out in another tweet, Vektor Grafix (developer of games including the ZX Spectrum conversion of the Star Wars arcade game) were based nearby at 46 The Calls. I'll get a proper picture of 23 The Calls the next time I pass through Leeds but in the meantime here's the Streetview link. Take a look at that view and compare it to the 1995 picture of Ian Oliver printed above; he's standing in front of the same building, so (massive assumptions ahoy) when Realtime closed Ian's next company Cross products, which he formed with Andy Craven of Vektor Grafix, was based in the same building.

When I got back to Leeds Station, the bloke on the phone had gone. I hope he found his taxi.

Does something bad happen to you whenever you go to Leeds? Are you inconvenienced by packs of stray dogs roaming the streets and disturbing passers-by? There's nothing I can do about it, but feel free to leave a comment or follow me on Twitter, @ShamMountebank

No comments:

Post a Comment